Yet Another DCOM Object for Command Execution Part 2

In the previous part we discussed how Impacket dcomexec works, the problems it has with newer Windows versions, how to fix them, and even how to bypass Defender. I also said I would cover a new DCOM object that can be used for lateral movement.

Today I present a new DCOM object that can be used for command execution and potential persistence. This technique abuses older initial-access and persistence methods involving Control Panel items.

We’ll start with Control Panel items, how adversaries have used them for initial access and persistence, and how they can be leveraged via a DCOM object to execute commands. Finally, we’ll cover detection strategies to identify and respond to this activity.

This part and the previous part are part of big research; you can find it here.

Control Panel Items as Attack Surfaces

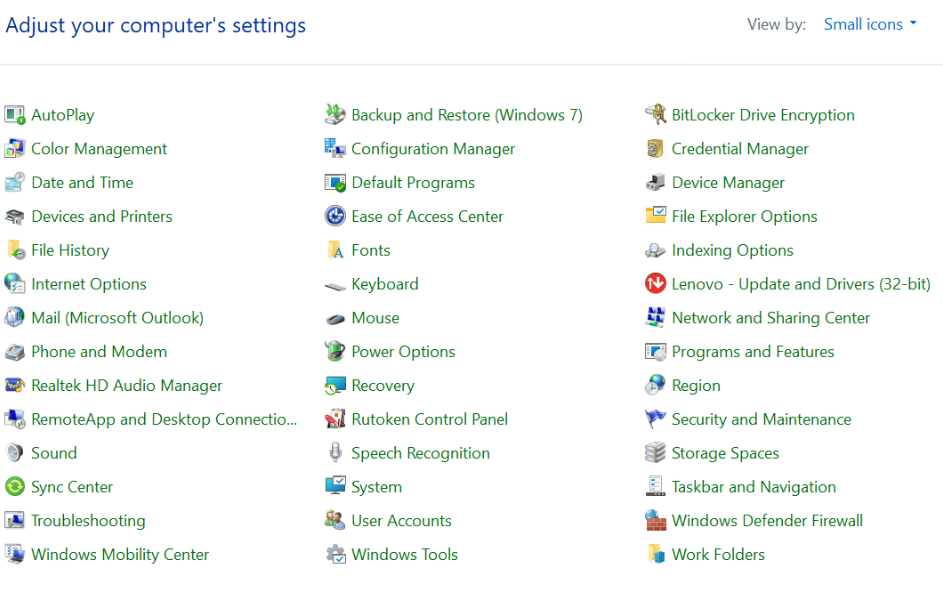

Control Panel items allow users to view and adjust computer settings (as shown in the figure below). These items are implemented as DLLs that export the CPlApplet function and typically have the .cpl extension. Control Panel Items can be executables as well but, in our research, we will concentrate on DLLs only.

Attackers can abuse CPL files for initial access (e.g., delivered via phishing and executed by the victim). When a user executes a malicious .cpl file, the system can become compromised — a technique mapped to MITRE ATT&CK T1218.002.

Adversaries may also rename malicious DLLs with a .cpl extension and register them in the Registry.

Under HKCU:HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

Under HKLM:

For 64-bit DLLsHKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

for 32-bit DLLs:HKLM\SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

these location plays a role if you want for this item to be available for the current logged in user or all users in machine.

However, the “Control Panel” sub key under HKCU should be created manually in addition to CPLs sub key unlike the “control panel” and “CPLs” subkeys under HKLM which is created automatically by the operating system.

Once registered, the DLL (CPL file) will load every time the Control Panel is opened, which can lead to persistence on the victim’s system.

It’s worth noting that even DLLs which do not comply with the CPL specification, do not export CPlApplet, or do not have the .cpl extension can still be executed via their DllEntryPoint function if they are registered under the Registry keys above.

There are multiple ways to execute Control Panel items:

- From cmd: control.exe yourfile.cpl

- By double-clicking the .cpl file.

Both of these ways under the hood use rundll32.exe:

rundll32.exe shell32.dll,Control_RunDLL yourfile.cpl

This calls the Control_RunDLL function from shell32.dll, passing the CPL file as an argument. Everything inside CPlApplet will then be executed.

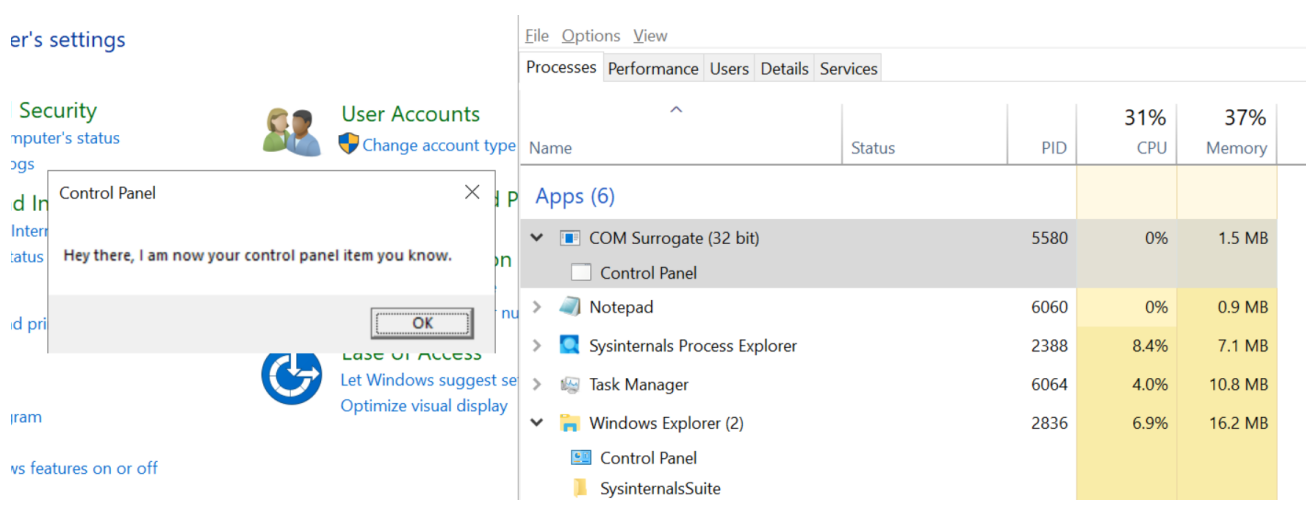

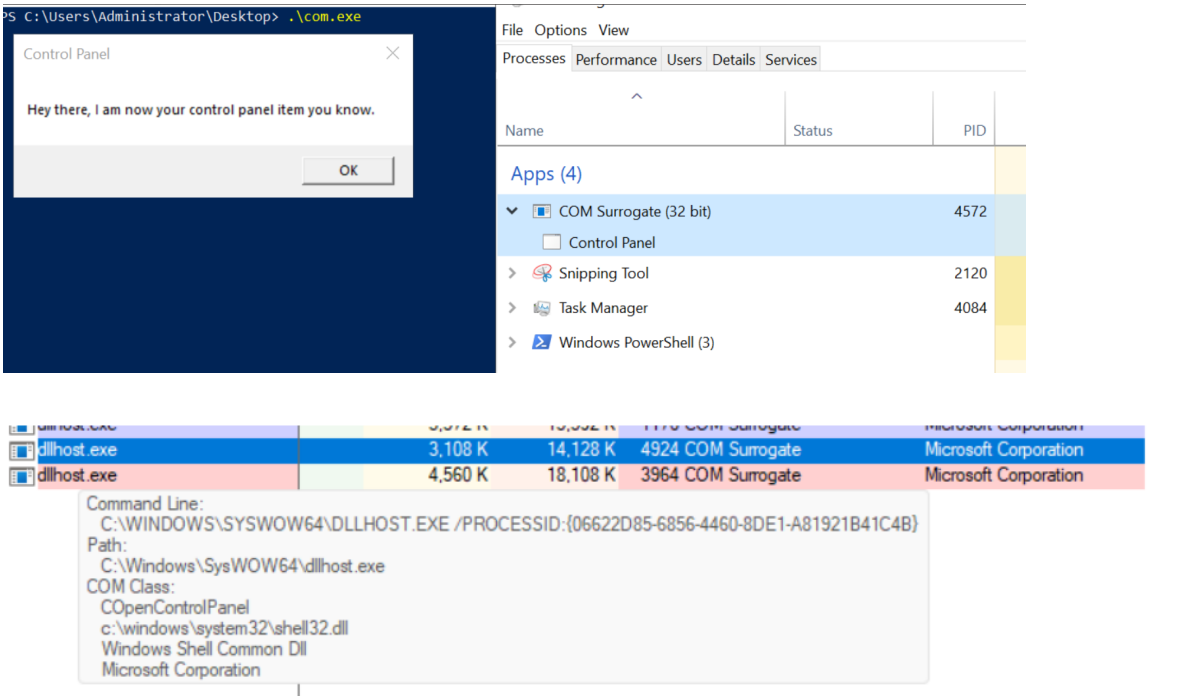

However, If the CPL file has been registered in the Registry as shown earlier, every time the Control Panel is opened, the .cpl file is loaded into memory through the COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe) as you can see in the photo below:

What happened is a control panel which has COM client will use COM object to load these CPL files

The COM Surrogate process exists to host COM server DLLs in a separate process, rather than loading them directly into the client process’s address space. This isolation improves stability for in-process server model. The hosting behavior can be configured for a COM object in the Registry if you want a COM server DLL to run inside a separate process.

we will talk about this COM object later

“DCOMing” Through Control Panel Items

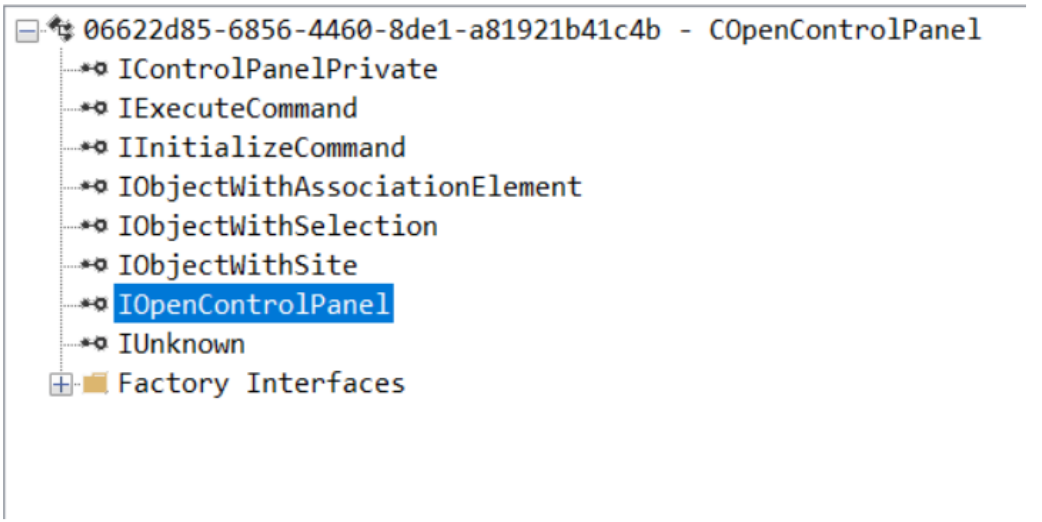

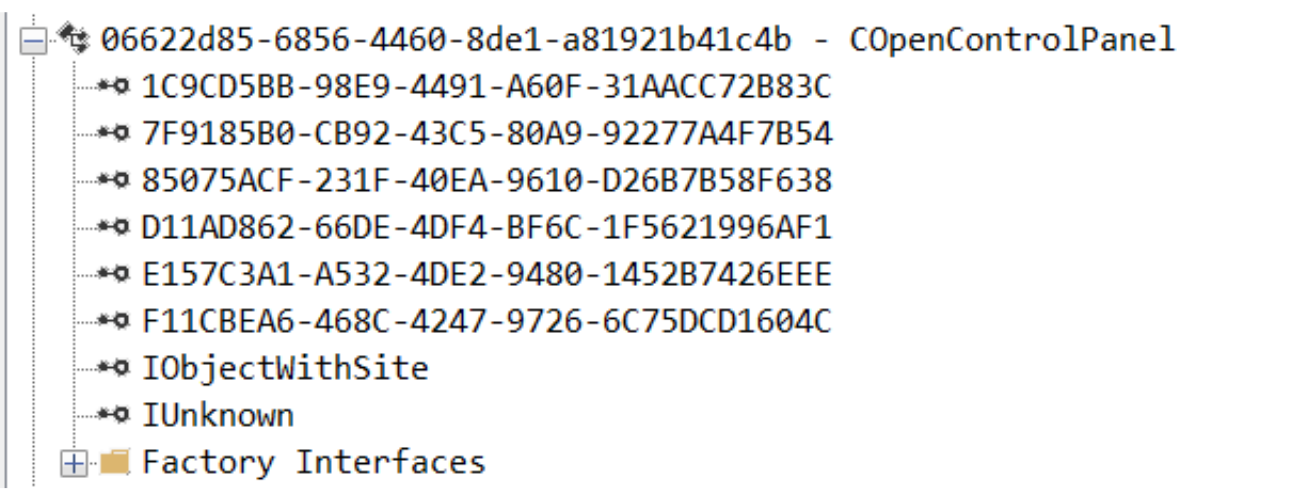

While following the manual approach of enumerating COM/DCOM objects that could be useful for lateral movement, I came across a COM object called COpenControlPanel, which is exposed through shell32.dll and has the CLSID {06622D85-6856-4460-8DE1-A81921B41C4B}. This object exposes multiple interfaces, one of which is IOpenControlPanel with IID {D11AD862-66DE-4DF4-BF6C-1F5621996AF1}, as shown in the OleViewDotNet output below.

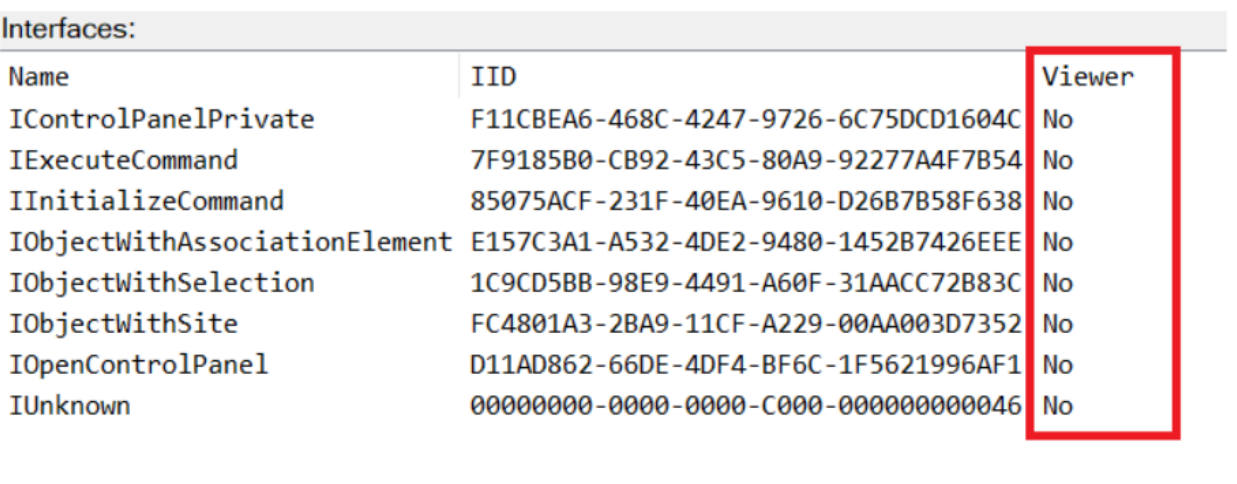

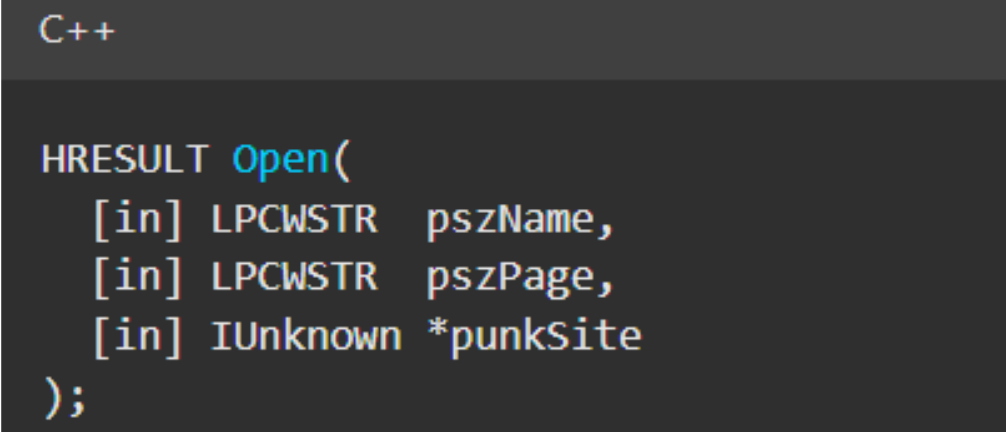

The idea of abusing Control Panel items came to mind immediately, so I wanted to check which functions were exposed by this interface. Unfortunately, both the interface and the COM class lack a type library, as shown in the screenshot below, which at first looked like a dead end since checking the interface definition would normally require reverse engineering.

However, it turned out that the interface is documented on MSDN, and according to the documentation, it exposes several functions one of them, called Open, allows the opening of a specified Control Panel item by using its name as first argument.

Full type and function definitions are provided in shobjidl_core.h.

It is worth noting that in newer versions of Windows (e.g., Windows Server 2025 and Windows 11), Microsoft has removed interface names from the Registry, which means they can no longer be identified through OleViewDotNet.

Returning to the COM object, I found that by using the Open function, it is possible to trigger a DLL to be loaded into memory if it has already been registered in the Registry. I registered my DLL and then created a simple C++ COM client to call the Open function on this interface.

From my testing, I made several observations:

- The DLL was indeed loaded into memory as expected. It was hosted in the same way as it would be when the Control Panel itself was opened, through the COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe). Using Process Explorer, it was clear that dllhost.exe loaded my DLL while simultaneously hosting the COpenControlPanel object alongside other COM objects.

- The DLL that needs to be registered does not necessarily have to be a .cpl file; any DLL with a valid entry point will be loaded.

- The open() function accepts the name of a Control Panel item as its first argument, but it appears that even if a random string is supplied, it still causes all DLLs registered in the relevant Registry location to be loaded into memory.

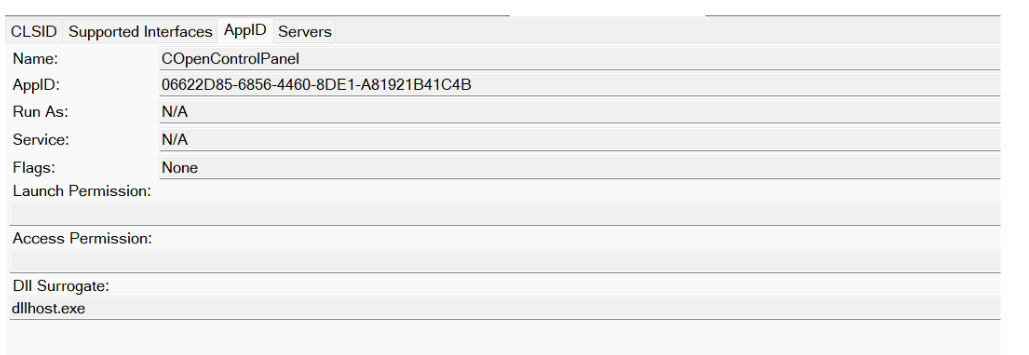

Now, what if we could trigger this COM object remotely, in other words, what if it is not just a COM object but also a DCOM object? To verify this, OleViewDotNet can be used to check the AppID of the object. As shown in the screenshot below

Both the launch and access permissions are empty, which means the object will follow the system’s default DCOM security policy. By default, this allows members of the Administrators group to launch and access the DCOM object.

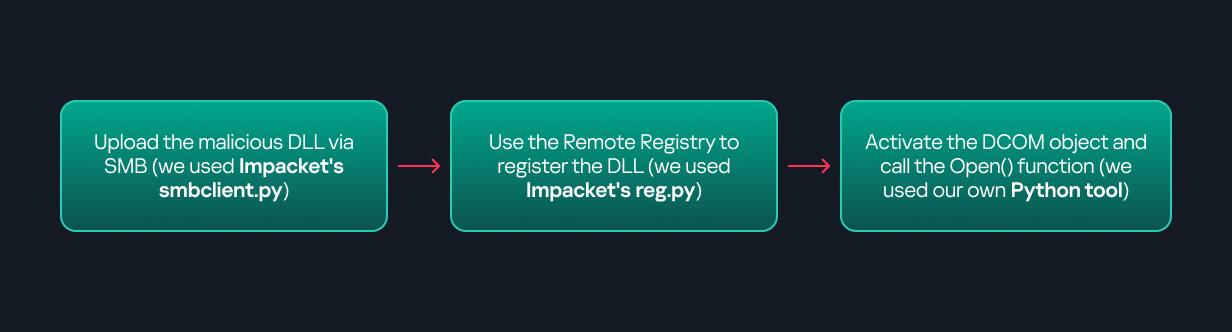

Based on this, we can build a remote strategy: first upload the malicious DLL, then use the Remote Registry service to register it in the appropriate Registry location, and finally use a trigger acting as a DCOM client to remotely invoke the Open() function, causing our DLL to be loaded. The flow of this approach is illustrated in the diagram below.

Regarding the trigger, it can be written either in C++ or in Python (for example, using Impacket). I chose Python because of its flexibility. The trigger itself is straightforward: you simply define the DCOM class, the interface, and the function to call. The full code example can be found here.

Once the trigger runs, you will observe the same behavior as when executing the COM client locally, your DLL will be loaded through the COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe).

As you can see, this technique not only achieves command execution but also provides persistence: it can be triggered in two ways: either when a user opens the Control Panel, or remotely at any time via DCOM

Detection:

The first step in detection is to check whether any Control Panel items have been registered under the following Registry paths:

- HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

- HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

- HKLM\SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

Most write-ups and guides online only mention the first path (the one starting with HKCU). For thorough coverage, it is important to monitor all of the above.

In addition, monitoring dllhost.exe (COM Surrogate) for unusual COM objects such as COpenControlPanel can provide indicators of malicious activity.

Finally, it is always recommended to monitor Remote Registry usage, since it is commonly abused for many types of attacks, not just in this scenario.

Conclusion:

In closing, I hope the information was clear and interesting. I have a few points I hope you will consider:

- As shown, DCOM represents a large attack surface. Windows exposes many DCOM classes and a significant number lack type libraries, so reverse engineering can reveal additional classes that may be abused for lateral movement.

- Changing registry values to register malicious CPLs is not good practice from a red-teaming ethics perspective. Defender products tend to watch common persistence paths, but Control Panel applets can be registered in multiple registry locations, so there is always a gap can be exploited

- Bitness also matters: on x64 systems, loading a 32-bit DLL will spawn a 32-bit COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe *32), which is unusual on 64-bit hosts and therefore a useful detection signal for defenders and an interesting red flag for red teamers to consider.