Yet Another DCOM Object for Command Execution Part 1

If you’re a penetration tester, you know that lateral movement is becoming increasingly difficult, especially in well defended environments. One technique for command execution has been the use of DCOM objects. The Impacket dcomexec.py script allows you to leverage three different types of DCOM objects: ShellWindows, ShellBrowserWindow, and MMC20. However, these objects are no longer as effective as they once were.

In this short blog post, I’ll explain which DCOM objects are still useful across different versions of Windows, which ones no longer work, and how we can fix or adapt them.

In the next section, I’ll also share a new DCOM object I discovered some time ago that can still be used for command execution.

In this blog post, I won’t dive deep into COM internals, I’ll leave that for my IPC series, where I discuss inter-process communication (IPC) in Windows.

So, let’s jump in!

ShellWindows

This DCOM object was one of the first to be discovered. It represents a collection of the open windows that belong to the Windows shell. It’s hosted through explorer.exe, so any client will communicate with this process.

The DCOM object implements the IShellDispatch interface, which exposes a function called ShellExecute. This function accepts multiple arguments (not in scope for this post).

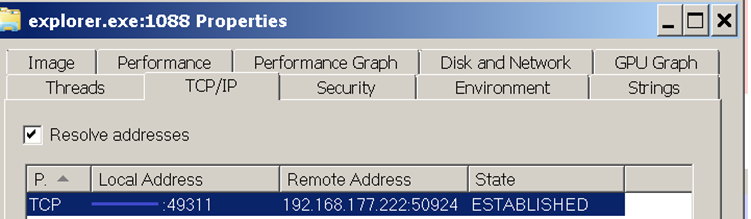

In the screenshot below, you can see how the connection is made to explorer.exe.

In the Impacket script dcomexec.py, after creating an instance of this COM object on a remote machine, the script provides a semi-interactive shell. Each time the user types a command, the function inside the COM object is invoked. The command output is redirected to a file, which the script then retrieves through SMB and displays back to the user to simulate a normal shell.

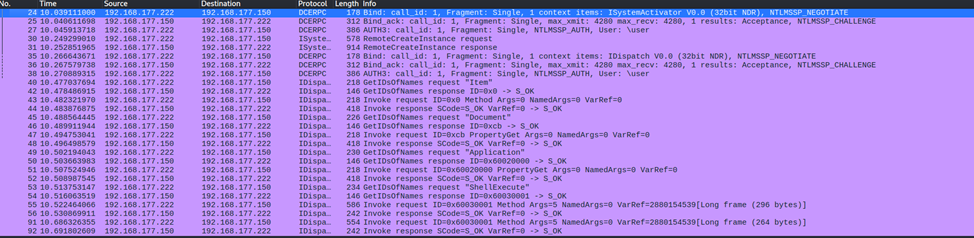

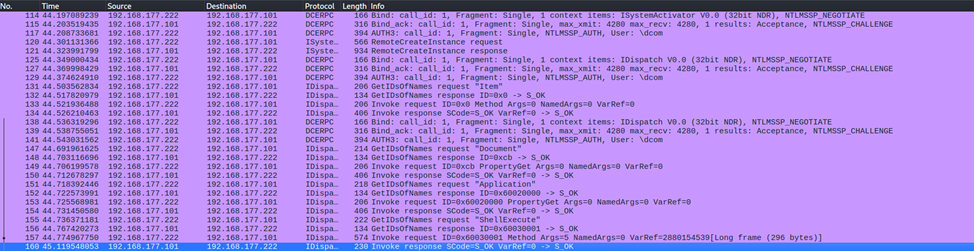

In the screenshot below, you can see the network traffic used to create the DCOM object.

Because the interface is inherited from IDispatch, functions are accessed using the Invoke function as the photo above.

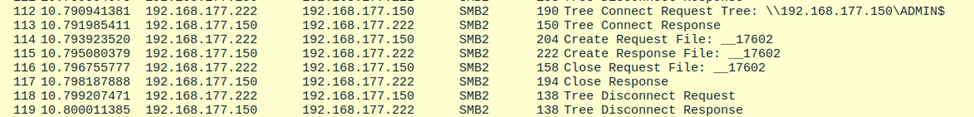

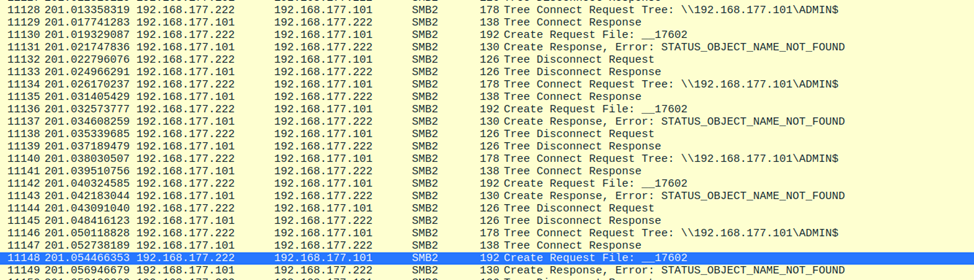

In the photo below, you can see that the script connects to SMB, specifically the ADMIN$ share, to open the file containing the command output. The output is stored under:

C:\Windows\__17602

Under the hood, the script uses this command when making the connection:

cmd.exe /Q /c cd \ 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\__17602 2>&1This sets the shell directory to C:\ and redirects the output to the ADMIN$ share under the filename __17602. Afterward, the script checks if the file exists; if it does, the execution is considered successful and displayed like a shell.

Behavior on the remote machine

On the remote host, the behavior is a bit strange. Each time you execute a command, the COM function is called, and because it’s exposed through explorer.exe, a flash popup of cmd.exe briefly appears. This is barely noticeable in Windows 7 and earlier, but very obvious in Windows 10 and 11.

Because of this, it’s only safe to use during engagements if you’re certain the user is not in front of their machine, otherwise, it’s not recommended.

Behavior on Windows 10/11

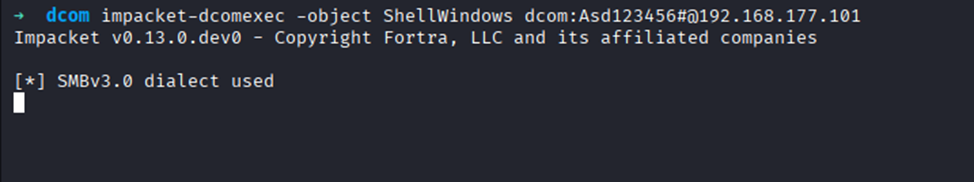

When running dcomexec.py against Windows 10/11 using ShellWindows object, the script hangs after showing the SMB banner as in the photo below.

Checking the network traffic shows that the DCOM object creation and method invocation appear successful as in the photo below.

However, if we inspect the SMB traffic:

The SMB client attempts to retrieve the output file from ADMIN$, but the file doesn’t exist. It retries several times until an error occurs. Meanwhile, on the target machine, you’ll still see a popup indicating that something was executed, but the output could not be written to the intended location.

From this, we can conclude that the DCOM object no longer has permission to write to ADMIN$.

To solve this, you can simply edit the script to redirect output to a directory where the COM object has write permissions, such as the Temp folder. A small edit in the code is enough to fix this.

You can check the enhanced script in my github

Moving forward, on Windows Server 2022 and 2025, this object no longer works at all.

ShellBrowserWindow

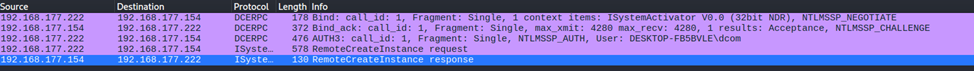

The ShellBrowserWindow object is almost the same as ShellWindows. However, in Windows 11 it no longer works, you’ll encounter the error:

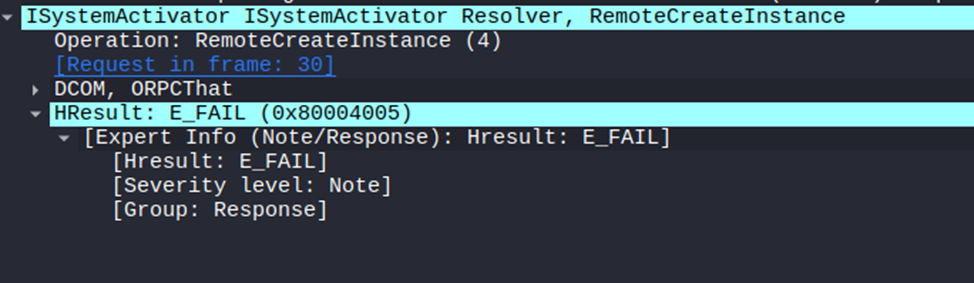

0x80004005 - E_FAILIf we check the traffic, it looks like this DCOM object can no longer be activated through ISystemActivator in newer Windows versions.

I won’t go into detail about why these objects fail or the exact meaning of the returned error. As I mentioned at the beginning, I don’t want to dive into COM internals in this series. We’ll keep those discussions for the IPC/COM series.

MMC20

The MMC20.Application COM object is the automation interface for the Microsoft Management Console (MMC). It exposes methods and properties that allow you to automate MMC consoles.

This object has historically worked across all Windows versions. However, starting with Windows Server 2025, if you attempt to use it, you’ll get a Defender alert and the execution will be blocked.

From the previous examples, you may remember that the script redirects execution output to a file under ADMIN$, with filenames beginning with __

OUTPUT_FILENAME = '__' + str(time.time())[:5]It appears that Defender checks for files written under ADMIN$ that begin with __, and if found, it blocks the process and alerts the user.

For quick fix: simply remove the double underscores (__) from the output filename, and you’re good to go.

In my version of the script, I already redirect output to the Temp folder, so it isn’t detected by Defender at all.

Hopefully, today I was able to show you the challenges with using DCOM objects for command execution. There may be other objects out there that I haven’t covered yet and that could be useful.

In the next part (which I hope to publish soon), I’ll share with you a new DCOM object I discovered that can still be used for command execution. Stay tuned!