Windows Inter Process Communication A Deep Dive Beyond the Surface - Part 9

Welcome to the next part of the IPC series, and the final part of the first wave of RPC series. In this post, we will look at the tools you can use to reverse-engineer an RPC server.

This part completes the last two articles where I talked about RPC research tooling. I began with external tools, then moved to internal tools. I split the internal tools into two groups: tools that don’t require reverse engineering (covered in the previous post), and tools that do. Today, we focus on the reverse-engineering side.

Sometimes, during research, you need to go deeper into how an RPC component works, whether it is a client or a server. Tools like RpcView are helpful, but they may not give you everything you need. You might want to inspect the security callback, understand the logic behind each server function, or see which authentication level the client is using.

In this post, I’ll share the approaches I use when reversing RPC servers. First, I will start with an automated tool that can perform some basic, high-level reverse engineering for you. After that, we will go deeper using IDA and look at how to reverse both RPC clients and servers.

So let’s dive in…

Testbed

For our testbed, we will use the client and server code shown here. We will compile both as 64-bit binaries, which gives us two executables: server.exe and client.exe. These will be the samples we reverse-engineer throughout this post.

Let’s take a quick look at the server code first.

Server Overview

The server listens over TCP port 41337:

status = RpcServerUseProtseqEp(

(RPC_CSTR)"ncacn_ip_tcp",

RPC_C_PROTSEQ_MAX_REQS_DEFAULT,

(RPC_CSTR)"41337",

NULL);It uses NTLM as its authentication provider:

status = RpcServerRegisterAuthInfo(

pszSpn,

RPC_C_AUTHN_WINNT, // NTLM

NULL,

NULL);The server also registers a security callback, and it sets the flagsRPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY | RPC_IF_ALLOW_CALLBACKS_WITH_NO_AUTH:

status = RpcServerRegisterIf2(

Example_v1_0_s_ifspec,

NULL,

NULL,

RPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY | RPC_IF_ALLOW_CALLBACKS_WITH_NO_AUTH,

RPC_C_LISTEN_MAX_CALLS_DEFAULT,

(unsigned)-1,

SecurityCallback);The security callback is very simple:

RPC_STATUS CALLBACK SecurityCallback(RPC_IF_HANDLE Interface, void* pBindingHandle) {

printf("The security callback is called");

return RPC_S_OK; // Allow any client that connects

}The interface exposes only one RPC function:

void PrintString(const char* str) {

printf("Received string: %s\n", str);

}Client Overview

Now let’s look at the client.

The client connects to the server over the network:

RpcStringBindingCompose(

NULL,

(RPC_CSTR)"ncacn_ip_tcp",

(RPC_CSTR)"192.168.177.177",

(RPC_CSTR)"41337",

NULL,

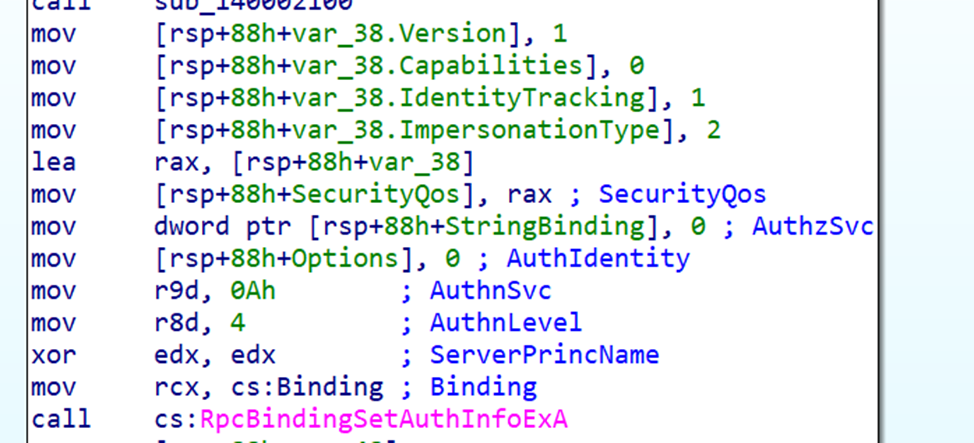

&stringBinding);It sets up a SecurityQOS structure and uses a high authentication level:

RPC_SECURITY_QOS SecurityQOS;

memset(&SecurityQOS, 0, sizeof(SecurityQOS));

SecurityQOS.Version = RPC_C_SECURITY_QOS_VERSION;

SecurityQOS.Capabilities = RPC_C_QOS_CAPABILITIES_DEFAULT;

SecurityQOS.IdentityTracking = RPC_C_QOS_IDENTITY_DYNAMIC;

SecurityQOS.ImpersonationType = RPC_C_IMP_LEVEL_IDENTIFY;

status = RpcBindingSetAuthInfoEx(

ImplicitHandle,

NULL,

RPC_C_AUTHN_LEVEL_PKT, // packet-level authentication

RPC_C_AUTHN_WINNT, // NTLM

NULL,

0,

&SecurityQOS);After setting the authentication info, the client calls the RPC function:

PrintString("Hello, RPC Server!");

Interface overview:

Finally, here is the interface UUID:

[

uuid(12345678-1234-1234-1234-123456789abc),

version(1.0),

]PE RPC Scraper

In the beginning I will show you how to use a high-level tool to handle basic reverse-engineering work. The tool we will use is PE RPC Scraper, which is part of Akamai’s RPC Toolkit. It’s a Python script that analyzes PE files and extracts RPC interface information. You can point it at a single file or let it scan an entire folder.

The script generates a JSON file that contains the RPC interfaces found inside the target DLL or EXE.

When you run the tool without extra options, it performs static PE parsing. In this mode, it gives you basic information such as:

- the interface UUID

- the number of functions

- function pointer addresses

- the role (client/server)

The tool also supports external disassemblers such as IDA Pro and Radare2. When you use the -d option, the tool can perform deeper analysis and extract more metadata, such as:

- interface registration sites

- registration flags

- security callback address (if found)

- security descriptor information

Now let’s try the tool on our test server and client.

Running the Tool on the Server (No Disassembler)

Command:

python pe_rpc_scraper.py server.exe

This creates a rpc_interfaces.json file with output like this:

{

"server.exe": {

"12345678-1234-1234-1234-123456789abc": {

"number_of_functions": 1,

"functions_pointers": [

"0x140001040"

],

"function_names": [

""

],

"role": "server",

"flags": "0x4000000",

"interface_address": "0x140016420"

}

}

}From this output, we can see that the tool successfully identified the interface by its UUID. It also detected that the binary exposes one RPC function, and it shows the address of that function and the role of the PE.

Running the Tool with IDA Pro Support

Now let’s run it with IDA Pro enabled:

python pe_rpc_scraper.py -d idapro server.exe

This time, the output includes an additional section called interface_registration_info:

"interface_registration_info": {

"0x14000113b": {

"interface_address": "0x140021120",

"flags": "0x18",

"security_callback_addr": "0x0",

"has_security_descriptor": false,

"security_callback_info": null,

"global_caching_enabled": true

}

}The new information shows the registration flags, which are 0x18. This can be mapped to:

0x8→RPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY0x10→RPC_IF_ALLOW_CALLBACKS_WITH_NO_AUTH

This matches our server’s source code.

However, the tool reports security_callback_addr: 0x0, which means it didn’t detect the security callback correctly. In our case, we know the server does have a callback, so this is a limitation of the tool.

Running the Tool on the Client

Now let’s check the client. We use the same command as before, but point it at client.exe:

{

"client.exe": {

"12345678-1234-1234-1234-123456789abc": {

"role": "client",

"flags": "0x0",

"interface_address": "0x1400163b0"

}

}

}The tool correctly identifies that the executable is an RPC client that connects to this UUID.

If we run the tool again with the IDA Pro option, no extra information is added. This is normal because the client does not register an RPC interface, it only consumes one, so there are no registration flags or callbacks to analyze.

IDA: Server Analysis

Now let’s load the server into IDA and see how it look.

If you open the server in IDA, the tool will take you straight to main, and everything is easy to follow. But in real cases, RPC servers are usually implemented inside DLLs, and they often expose multiple interfaces. Sometimes one DLL contains several servers. Because of that, we need a more systematic way to reverse-engineer RPC servers.

The first thing I like to do is identify the RPC interface registration functions, because they reveal the UUIDs of the exposed interfaces.

To start, I search for RPC registration APIs.

If we open the Imports tab and type “RPC”, we will see functions like:

RpcServerRegisterIf2RpcServerUseProtseqEpARpcServerRegisterAuthInfoA- etc.

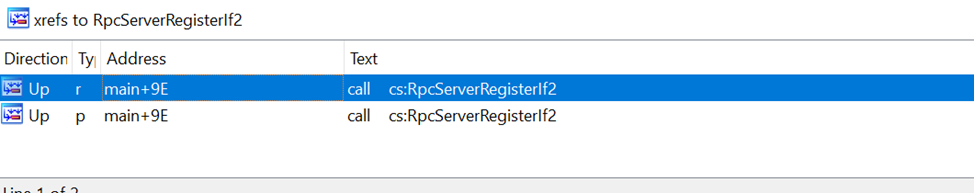

If we cross-reference RpcServerRegisterIf2, IDA shows us where this function is called inside the server binary.

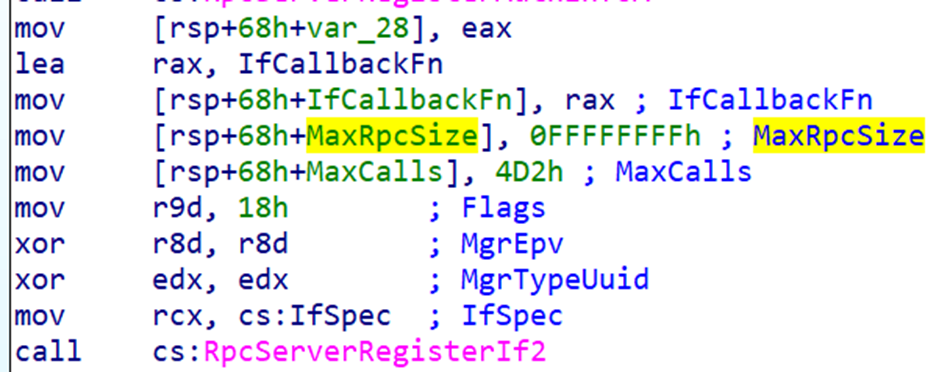

IDA also shows the actual function arguments as comments, which is very helpful.

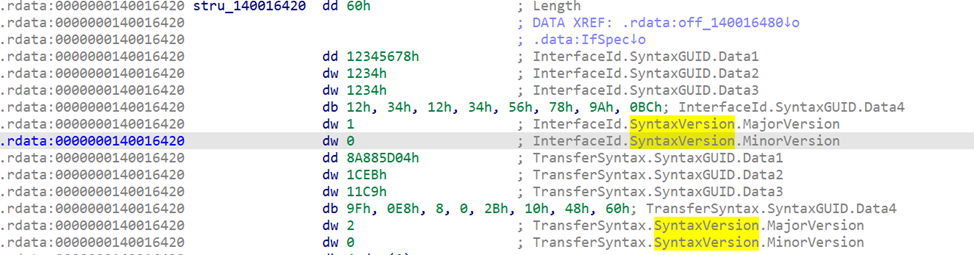

Identifying the Interface UUID

Our first task is to identify the interface UUID.

The UUID is located inside the RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE structure, which is passed as the first argument to RpcServerRegisterIf2. IDA usually names this pointer IfSpec.

This structure is automatically generated by the MIDL compiler and stored in the server stub.

The structure looks like this (from rpcdcep.h):

typedef struct _RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE {

unsigned int Length;

RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER InterfaceId;

RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER TransferSyntax;

PRPC_DISPATCH_TABLE DispatchTable;

unsigned int RpcProtseqEndpointCount;

PRPC_PROTSEQ_ENDPOINT RpcProtseqEndpoint;

RPC_MGR_EPV* DefaultManagerEpv;

const void* InterpreterInfo;

unsigned int Flags;

} RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE, *PRPC_SERVER_INTERFACE;Inside it, the InterfaceId member is another structure:

typedef struct _RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER {

GUID SyntaxGUID;

RPC_VERSION SyntaxVersion;

} RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER;The first member is the interface UUID and the second is the version.

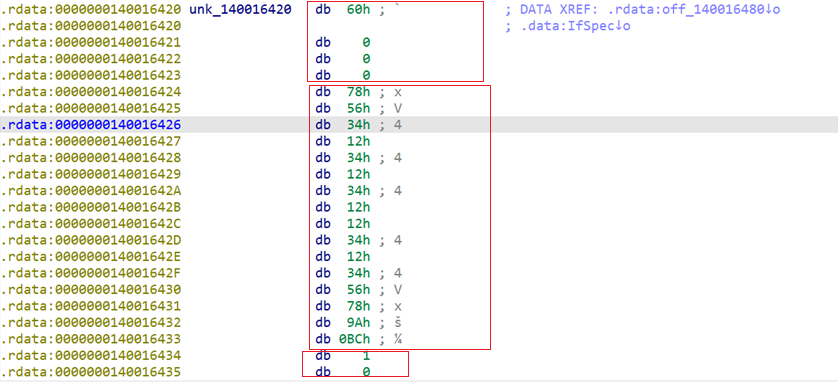

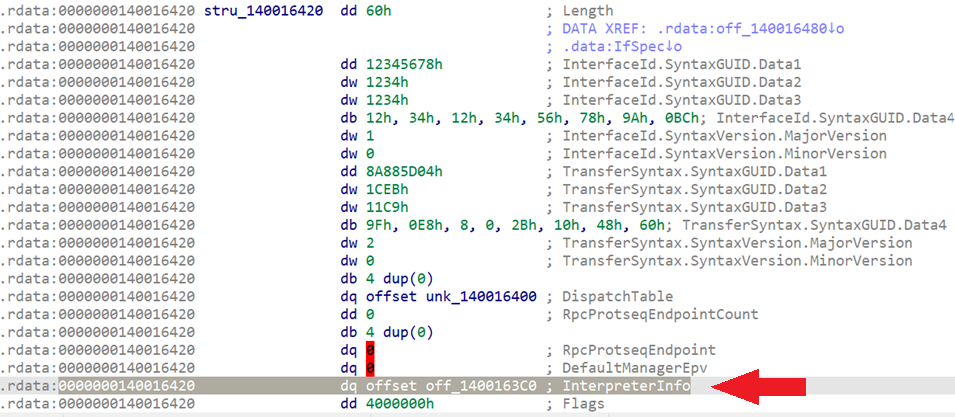

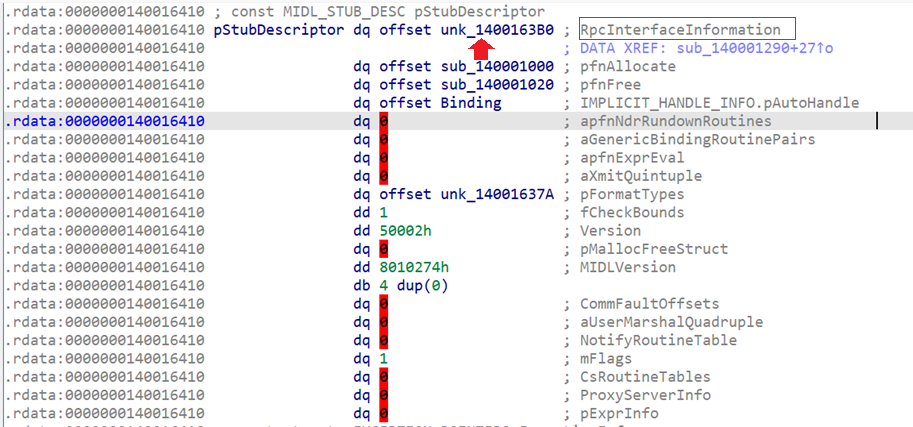

If we go to the address of IfSpec in IDA, we can see the raw bytes that represent this structure.

You can see:

- The first 4 bytes → size of the struct

After that we have RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER struct:

- The next 16 bytes → the interface UUID

- The next 2 bytes -> the version (minor, major)

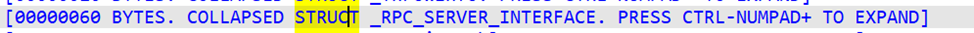

To make life easier, you can open the Structures tab and create an instance of _RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE (IDA already has this structure defined). After applying it, IDA will parse everything nicely.

The size of this structure is 0x60 bytes (96 decimal).

Now IDA shows the fields clearly, including the interface UUID (GUID).

Checking the Registration Flags and Security Callback

Back in the registration call, we can check the registration flags.

In our case, IDA shows the flags value 0x18, exactly as the Python script reported.

0x18 =

0x8→RPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY0x10→RPC_IF_ALLOW_CALLBACKS_WITH_NO_AUTH

This matches the source code.

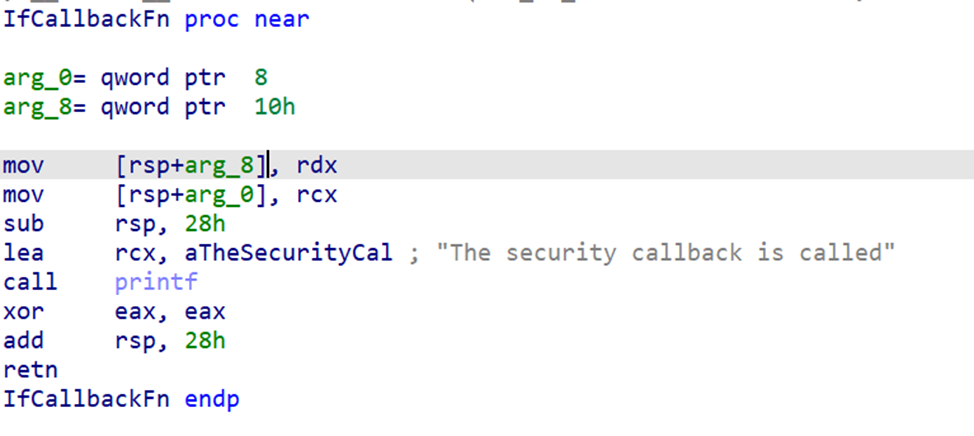

Now the final thing related to registration is the security callback.

The callback pointer appears in the argument list of RpcServerRegisterIf2 as IfCallbackFn.

When we double-click the callback pointer, IDA takes us directly to its function body.

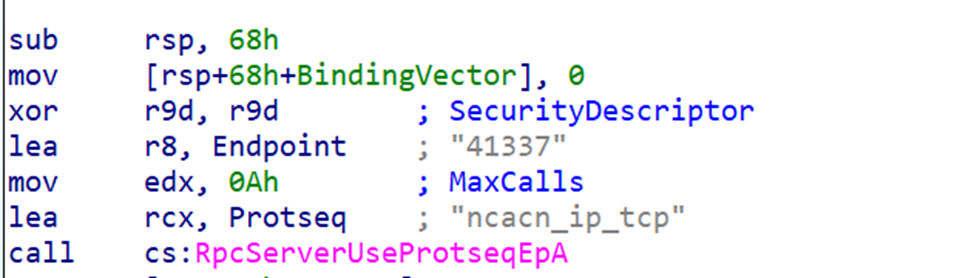

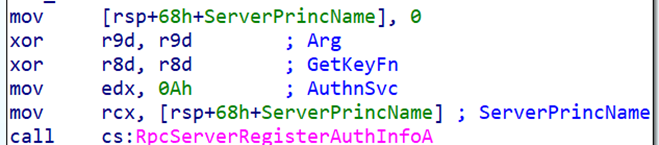

More Useful Functions Around the Server

Near the registration call, we can usually find other important RPC initialization functions. For example:

RpcServerUseProtseqEpA→ tells us how the server is exposed (the endpoint)

RpcServerRegisterAuthInfoA→ shows the authentication provider (NTLM)

These functions appear close together because the compiler emits the RPC setup in one block.

Finding the Exposed Server Functions (PrintString)

The next important task is finding the functions exposed by the server stub.

These live inside the MIDL server interpreter structures, which point to the dispatch table.

The server interface struct RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE contains a pointer called InterpreterInfo:

typedef struct _RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE {

unsigned int Length;

RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER InterfaceId;

RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER TransferSyntax;

PRPC_DISPATCH_TABLE DispatchTable;

unsigned int RpcProtseqEndpointCount;

PRPC_PROTSEQ_ENDPOINT RpcProtseqEndpoint;

RPC_MGR_EPV* DefaultManagerEpv;

const void* InterpreterInfo; ------------> This one

unsigned int Flags;

} RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE, *PRPC_SERVER_INTERFACE;which points to a MIDL_SERVER_INFO structure:

typedef struct _MIDL_SERVER_INFO_ {

PMIDL_STUB_DESC pStubDesc;

const SERVER_ROUTINE* DispatchTable;

PFORMAT_STRING ProcString;

const unsigned short* FmtStringOffset;

const STUB_THUNK* ThunkTable;

PRPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER pTransferSyntax;

ULONG_PTR nCount;

PMIDL_SYNTAX_INFO pSyntaxInfo;

} MIDL_SERVER_INFO;

This structure is also generated by the MIDL compiler.

The most interesting field is:

DispatchTable: pointer to dispatch table that contains pointers to the server functions

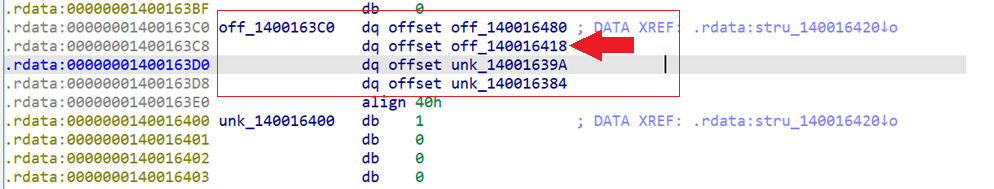

If we go to the _RPC_SERVER_INTERFACE struct in IDA, we can find the pointer to _MIDL_SERVER_INFO

If we follow that address, IDA shows the pointers inside this struct

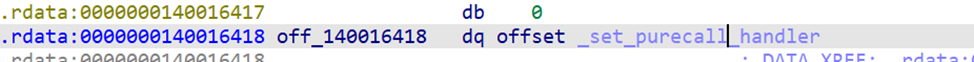

The second entry is the dispatch table pointer.

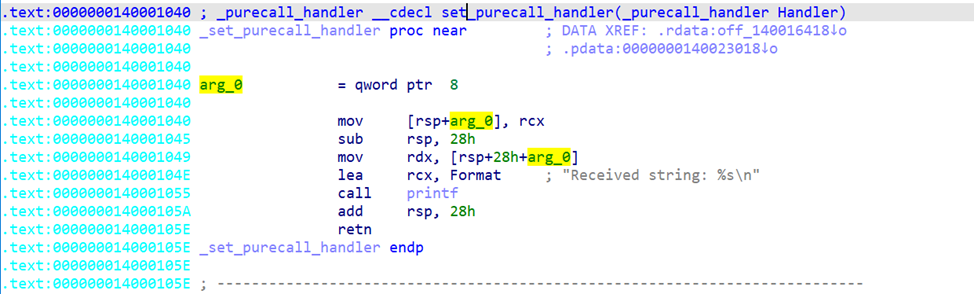

If we follow that pointer, we land directly on the address of the RPC-exposed function — in our case, PrintString.

This is how we identify every function implemented by the server stub.

It looks complicated at first, but we will break this down more in the upcoming static analysis part from RPC series.

IDA: Client Analysis

For the client, we usually cannot extract as much information as we can from the server, but there are still some useful things to look at.

Just like before, in the Imports tab we search for “RPC”.

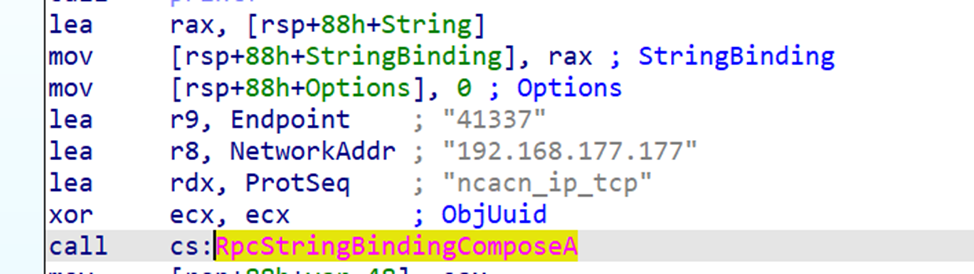

A good place to start is the string binding call RpcStringBindingComposeA.

IDA automatically annotates the arguments and shows the IP address, port, and protocol sequence.

IDA also identifies the QoS structure and the authentication settings.

The most important part of the client is identifying which interface UUID it binds to.

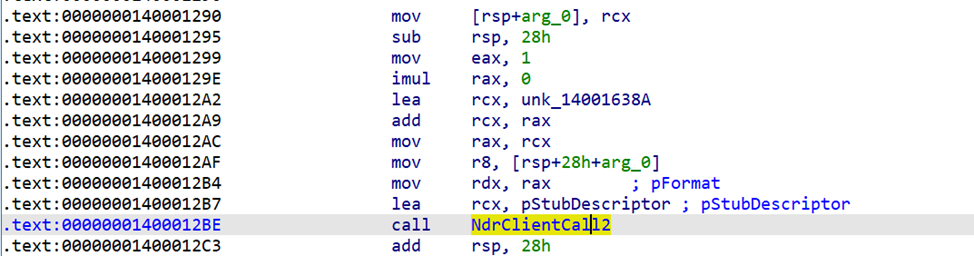

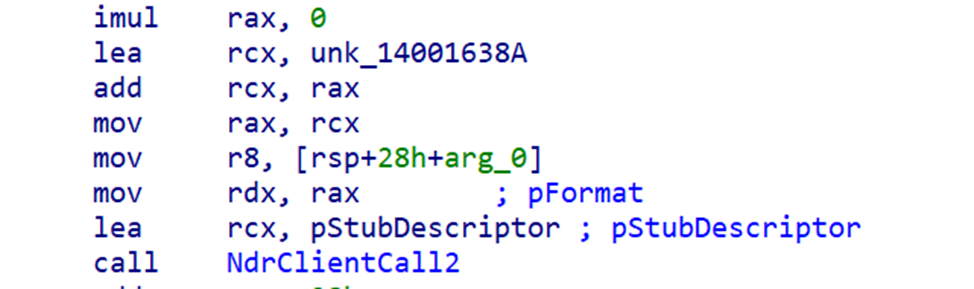

The MIDL compiler generates calls to the RPC runtime, usually one of the NdrClientCall* functions.

If we search for NdrClientCall in the imports and cross-reference it, IDA takes us to the client stub.

The function definition is:

NdrClientCall2(

PMIDL_STUB_DESC pStubDescriptor,

PFORMAT_STRING pFormat,

...

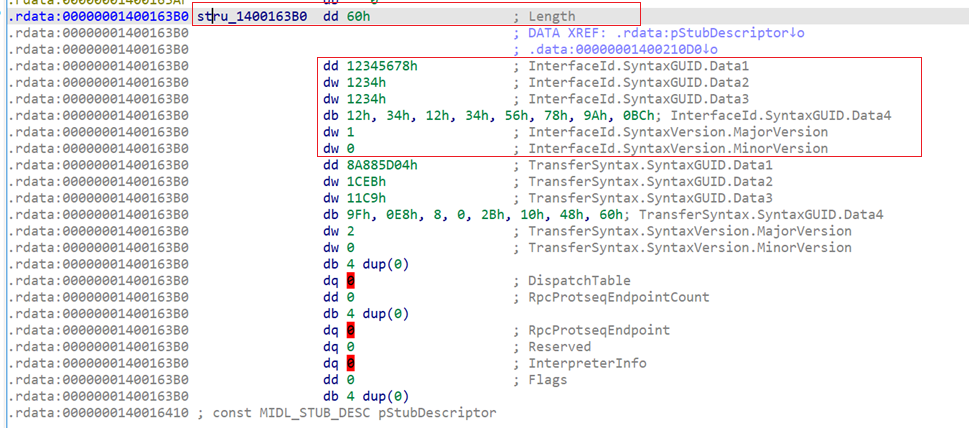

);pStubDescriptor→ points to theMIDL_STUB_DESCstructure- Inside it, the first member is a pointer to an

RPC_CLIENT_INTERFACEstructure which is very similar toRPC_SERVER_INTERFACE

typedef struct _RPC_CLIENT_INTERFACE {

unsigned int Length;

RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER InterfaceId; // ← UUID here

RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER TransferSyntax;

PRPC_DISPATCH_TABLE DispatchTable;

unsigned int RpcProtseqEndpointCount;

PRPC_PROTSEQ_ENDPOINT RpcProtseqEndpoint;

ULONG_PTR Reserved;

const void* InterpreterInfo;

unsigned int Flags;

} RPC_CLIENT_INTERFACE;Again, the second field (InterfaceId) is a struct that contains the UUID and the version:

typedef struct _RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER {

GUID SyntaxGUID;

RPC_VERSION SyntaxVersion;

} RPC_SYNTAX_IDENTIFIER;Let's come back to IDA and follow pStubDescriptor which is pointer to MIDL_STUB_DESC structure and Apply the correct type, IDA resolves everything cleanly.

Following the first pointer takes us directly to the struct RPC_CLIENT_INTERFACE that contains multiple members and the second is the interface UUID (The first member in MIDL_SERVER_INFO struct).

This is how we confirm which interface the client is targeting.

I know the IDA part was a bit complicated and full of structures we haven’t fully explained yet, but I wanted to show it now because these structures are extremely useful when reversing any RPC server or client. Don’t worry, we will revisit all of them in the next parts and go through every detail slowly and clearly.

I hope this final part of the first wave was clear enough, and I hope you enjoyed this introduction to RPC. I wanted to share some of the knowledge I have and present it in a simple way so anyone can start learning this very complex topic.

But we are not done yet — in fact, we have barely started. The next wave will contain a lot more information about RPC, including topics that are not documented anywhere by Microsoft.

So, see you next year in the second wave!